The exodus from East to West Germany in 1989 has brought back memories to Erika Talaska, for she also made her escape in 1954. At age 15, she boarded a train out of her hometown of Schmolln, 40 miles south of Leipzig, Germany's second largest city. She took the train as far west as it would go, and reached the border city of Eisenach. Eisenach is where Erika sometimes vacationed. Erika would stand and view West Germany from Wartburg Castle. It was within sight of this castle where Erika made her escape. On the train she met another woman, also seeking freedom. Together they reached the border, waited till dark, and walked at night. They reached West Germany and got on another train, and went as far west as they could go. Erika went on till she came to a town close to Luxembourg. She thought the furthest west she could go, the safer she would be. "You see on television how the people are now waiting in camps," she said, speaking of East Germans entering in the west in 1989. "I didn't do any of that. I was illegal," she said.

Wartburg Castle, Eisenach, Former East Germany

Erika got a newspaper and found a job as a housekeeper/nanny for a family. They knew where Erika had come from, and began harassing her to go back to her mother. West Germany was not too obliging to East German refugees and the family Erika was staying with did not want to get in trouble. "They harassed me constantly. So, I left," she said. Erika changed jobs frequently, so her address could not be traced. About a year after she had first left her hometown, she crossed back over into East Germany to see her mother, and snook out the same way she had the first time. "There were loopholes in the early days," Erika said of the security, consisting of a wall (sometimes barbed-wire and posts), dogs and security towers with armed guards. Erika said had she been caught, she feels like they would have just kept her in the East, and kept an eye on her. She admits, though, that she could also have been shot.

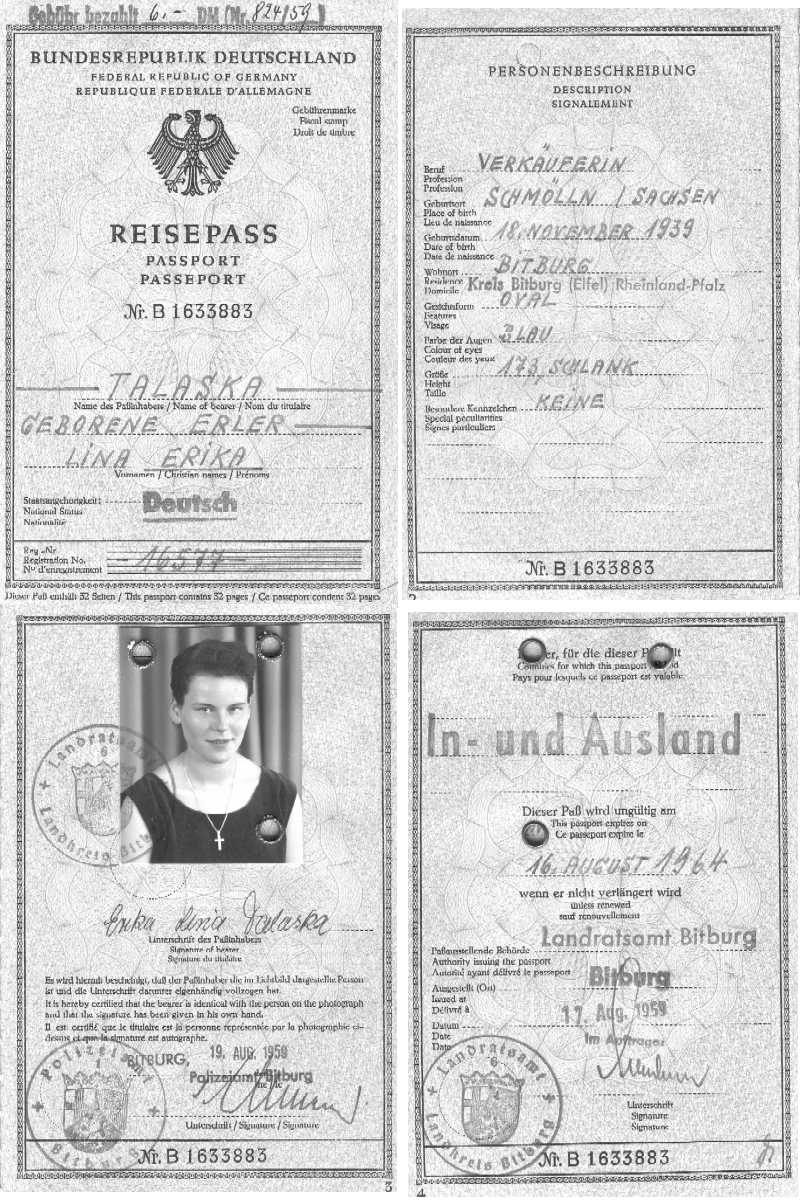

Finally, she got a West German passport, became legal and got a job as a bookkeeper (and/or cashier?) at an American Air Force base in Spangdahlem. She met serviceman Leo John Talaska there. They, married, and she eventually obtained a VISA and came to the U.S. in 1959. Why had Erika, at age 15, left her family, with only the clothes she had on and just enough money for train fare? "For anyone else, it's hard to understand," she said.

Erika was born in a country in the midst of WWII. "From the time I was born, until kindergarten I stayed a lot in the basement," she said. Her town got shelled by Russians, then by the U.S., then by Russia again. When she was very young, her father, Rudolf Erler, was drafted in to Hitler's army, as was every male between the ages of 14-65. "It was either be drafted or be shot at gunpoint," she said. Her father was sent to the Russian Front, and Erika and her family never heard from him again. A friend said her father had been shot in the arm. Erika believes her father survived and was one of 25,000 POWs the Russians had kept because Rudolf was a talented engineer. Erika's mother, Lotte declared Rudolf dead so that she could obtain social security benefits. According to the death certificate, Rudolf was killed in action in Pampali, Republic of Latvia (formerly western Russia) on December 22, 1944. "I despise Hitler more than anyone," Erika said, "because he's the reason for my father being sent away," Erika reminisces the atrocities of WWII and says, "We (German military) did terrible things. But we've paid for it."